From the age of 30, Angela Mock knew something was horribly wrong inside her.

The Port Coquitlam, B.C., resident was living in excruciating pain that, by 2020, had taken both her and her husband away from work to care for her and their three kids. Bedridden for days at a time, Mock said she had “constant burn marks” from the heating pad she carried everywhere.

“Bladder, lower back, lower abdomen, lots of bowel pain … I felt like someone was constantly stabbing me from the inside out,” she recalled.

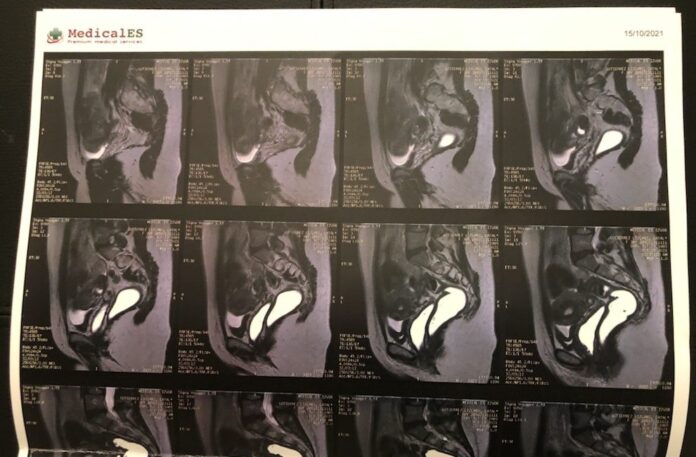

An MRI would later reveal her endometriosis had progressed, consuming her pelvic organs to the point where only “about three millimetres” of healthy colon tissue remained.

She said she was told her bowel could rupture and that her colon needed to be removed – the words “irreversible” and “colostomy bag” ringing in her ears.

“I knew it was bad. I didn’t know it was that bad at that point … it was a very blunt conversation.”

Mock didn’t want to accept that as her only option. Someone suggested she search for an alternative outside Canada, and after consultations with clinics in Germany, the U.A.E., the U.K., and the U.S., she settled on one in Romania.

The Bucharest Endometriosis Center was well-reviewed by other patients in Facebook groups dedicated to information-sharing about the disease, and Mock was on a plane a month later. Her six-hour operation in 2021 included five surgeons at an out-of-pocket cost of $9,500, plus about $3,000 in meals, accommodations and flights.

“He removed over 30 different endometriosis masses inside me. He worked on my kidneys, my bladder, my ovaries, my sacral roots, my rectal wall, and obviously, my bowel,” Mock said.

“I know it sounds dramatic, but he literally saved my life.”

Kolbi Morley of Halifax was an avid traveller before her endometriosis pain intensified in her 30s. She was diagnosed by laparoscopy in February 2022.

Courtesy: Kolbi Morley

Atlantic Canada’s first multidisciplinary endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain clinic is now up and running at the IWK Health Centre in Halifax, but its lead physician, Dr. Elizabeth Randle, said the waitlist is at least a year. Every effort is made to speed up the process for those in urgent need, she added, but the disease can get worse the longer a patient waits.

“It’s not uncommon for patients, by the time they are being seen by specialty and subspecialty physicians, to have more extreme presentations,” Randle explained.

“This type of complex disease process really does require a team of specialists who can approach it to manage it in the best way … We definitely need more of everything in order to be able to provide the care that we’re seeing the demand for.”

Singh said he respects a patient’s choice to go abroad if they can’t get timely treatment in Canada, but worries about them getting proper follow-up care for a condition that necessitates a “lifelong relationship” with the health-care system.

Endometriosis costs the health-care system an estimated $1.8 billion each year.

More resources for education, training and care – including dedicated operating room hours in hospitals – are needed, patients said, as well as more compassion and validation from doctors.

Catalina Lizcano, who lives in Montreal, said she advocated for excision surgery to treat her debilitating pain for years, but was told cryptically by several physicians there was “no point” unless she planned on having children. She said she also lost a job because of how much time off she took to manage her symptoms, and would like to see endometriosis recognized as an “illness that causes disability,” with protections in the workplace.

“I reached the point of being in pain three weeks out of four,” Lizcano recalled.

“I was calling in sick so often at work, I couldn’t do anything. I couldn’t walk my dog, I couldn’t cook … I could do nothing other than try to keep going.”

Read more:

‘Phenomenal’: Patients welcome Atlantic Canada’s first multidisciplinary endometriosis clinic

Both Singh and Leonardi said they – and others in the field – are working to change a culture that has historically sidelined and stigmatized the health concerns of female, transgender and non-binary patients, but everyone has a role to play.

“To hear these stories breaks my heart … I hear this every single day in my clinical scenarios,” said Singh.

“The responsibility lies among all of us. The patients are speaking up – fantastic. I need to speak up. The SOGC needs to speak up.”

In his own practice, Leonardi said he now adds a line at the end of a patient’s report that says something like, “Just because today’s ultrasound is normal doesn’t mean the patient is normal … and this should not be the last point of investigation or validation for the patient.”

The SOGC, meanwhile, is developing a new endometriosis guideline, and the Canadian Association of Radiologists is working on a consensus paper to advance awareness and education for members.

Endometriosis expert shares challenges and solutions for patient woes in Canada

Last year, Ontario’s Bill 273 formally declared March as Endometriosis Awareness Month, and this year, Vancouver-area MP Don Davies introduced a private members’ motion in the House of Commons calling for a national action plan. Australia has such a plan, and similar strategies are being discussed in France and the U.K.

“It’s time to put the focus and the resources and the finances behind funding endometriosis awareness (and) endometriosis support,” said Kate Luciani, executive director of The Endometriosis Network Canada.

“The trickle-down effect – we hope – means faster access to surgery, faster access to care, (and) getting this care in places that you don’t normally get it.”

Speaking to Global News, federal Health Minister Jean-Yves Duclos did not say whether Ottawa would consider a national plan, but that it wants to continue listening to patients and researchers.

“Obviously, a lot of that responsibility falls in the domain of provinces and territories because it deals with the provision of health-care services. When it comes through the data and analysis of research, the federal government has an important responsibility to keep the capacity.”

Health ministers in Alberta and Ontario did not respond to requests for comment by deadline. Nova Scotia’s health minister declined a request, and B.C.’s health minister was not available.

More than a year after her successful operation, Mock encouraged governments to consider how other countries treat endometriosis with a mix of public and private services.

“It’s great that we have free public health care, but we should be able to have a choice,” she said.

“This could be prevented in really, really young ages of women and teens, and it is something that should be more carefully looked at and funded in our medical system.”

Mock said she knows that even after her surgery in Romania, there’s a chance the endometriosis could resurface. Until then, however, she will enjoy her new quality of life – with a new memory to overshadow the words “irreversible” and “colostomy bag.”

“I had my first shower after the surgery and it was like, the most amazing one ever,” she said with a smile. “I just stood in there and I was just sobbing because I felt like finally, somebody took me seriously and did something about it.”