Journalist Ziar Khan Yaad and his cameraman had just set up their equipment outside a mosque in Kabul when an armoured Land Cruiser screeched to a halt beside them.

It was August 2021, about two weeks since the collapse of the Afghan government, and Yaad, a broadcaster for 24/7 news channel Tolo News, was reporting on the country’s struggling economy since the Taliban takeover.

Every day, low-skilled workers arrived at Haji Yaqub Mosque to find manual labouring jobs. Yaad was partway into an interview with one of them when a group of men, claiming to be Taliban, launched themselves out of the Land Cruiser and towards him.

After confiscating all of their equipment and phones, Yaad was beaten by several of the men. When he identified himself as a journalist, it made the men angrier, and the blows harder.

Left bruised and wheezing on the side of the road, Yaad knew his days were now numbered. An outspoken critic of media censorship and supporter of women’s rights and freedom of speech in the country, his parents urged him to leave.

And so he did. With the help of an NGO, Yaad was flown to Islamabad in September 2021, where he was invited to apply for Canada’s resettlement program for vulnerable Afghans.

But he has remained there ever since.

“(When we did our) biometrics, we were told that our flight will take within three weeks or up to one month. But now we have spent five months after the biometrics,” Yaad tells Global News.

“We are afraid, because if you do not have a legal visa in Pakistan, the police may arrest you. There are even fears of imprisonment and deportation back to Afghanistan.”

Ziar Khan Yaad, an Afghan journalist, says he has been waiting for resettlement in Canada for six months.

Yaad is one of thousands of refugees who fled to Pakistan when Afghanistan fell under Taliban rule and now find themselves stateless, homeless and broke as they await resettlement in Canada.

Many of those in Pakistan have long been approved for resettlement by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), but have received no information as to when that will be.

IRCC has brought in just one-quarter of the 40,000 refugees it pledged to bring to Canada in July last year. But it says it is doing everything it can in a complicated environment.

Global News spoke to half a dozen families in limbo in Pakistan, many of whom say they have almost run out of money, cannot afford food, have expired visas or no passports and are depressed.

“Being in Pakistan for me and for other people is a very bad feeling,” another journalist, who has just returned to Afghanistan after months in Pakistan, says. Global News is not naming him due to fears for his safety.

Canada will honour refugee commitments on ‘a moral basis’: immigration minister

The man has lung cancer and had his leg amputated in Pakistan after an injury sustained while fleeing the country. He is desperate to get to Canada to get better medical treatment.

“The situation is not clear, the future is not clear and also we have no country, no land, to live (in Pakistan). It’s a very bad feeling. I can’t describe it, it’s indescribable,” the man says.

“Some people say after the war in Ukraine, the government of Canada decided to take the people of Ukraine to Canada … and they’re forgetting the people of Afghanistan.

“We are forgotten now.”

In July 2021, the federal government unveiled a new, expedited “path to protection” for Afghans who supported Canadian troops as interpreters, cultural advisers or support staff, as well as their families. It came after weeks of criticism from angry Canadian veterans upset Ottawa wasn’t doing more to help Afghans facing possible Taliban reprisals for having worked with Canada in the past.

Included in the 40,000 people Canada has pledged to take in are 5,000 referred through a partnership with the United States, such as Yaad.

When he was invited to apply for resettlement to Canada by IRCC on Oct. 24, he was thrilled.

“I’m going to YouTube and searching about Toronto … and about Niagara Falls. I am imagining walking around (them),” he says from a sparse bedroom in Islamabad over Zoom, a huge smile plastered across his face.

“I’ve heard that (in Canada) there is a respect for the people, for humanity and you are not feeling like a refugee. You are feeling like this is your own country.”

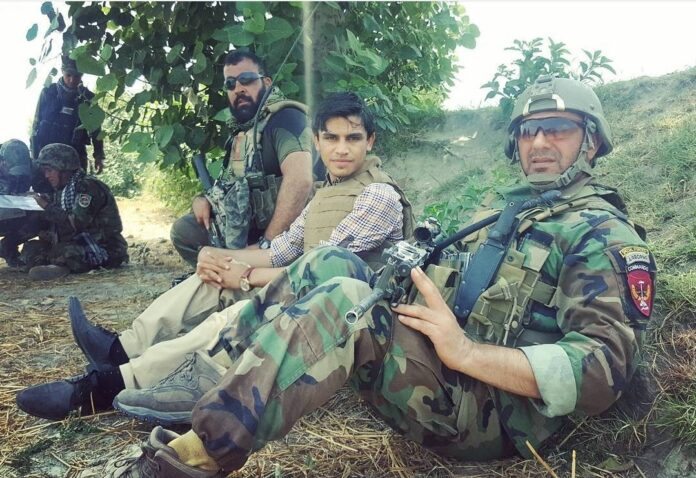

Yaad at work in Afghanistan for Tolo News.

But that smile fades when Yaad speaks of the months since, money and hope dwindling, as he and his now-pregnant wife plead with Canada for answers about when they will be allowed in.

Yaad had his biometrics (fingerprints and photos) done in November.

“This is a difficult situation for Afghans because our lives are in danger in Afghanistan and … we come to the third countries in a situation where we don’t have money, we don’t have enough financial support to have accommodation, to have some food,” he says.

“When we are emailing to the IRCC … they’re just saying, ‘Wait, your case is still in process.’ And some of our colleagues who come after me and they’ve done their biometrics after me, now they’re in Canada.”

Afghan journalist stranded in Islamabad waiting for IRCC application processing

Yaad is being supported by an NGO, the Committee to Protect Journalists, which flew him to Islamabad and offered accommodation assistance. However, that support ran out at the end of March and Yaad says he has little more than US$25 to his name. Both his and his wife’s Pakistani visas are now expired.

He has since moved from Islamabad to Peshawar, on the Afghanistan border, because it’s cheaper. He worries about his wife’s pregnancy and the doctors’ visits they cannot afford.

But he cannot return to Afghanistan. He says he is “not the first and last journalist” to be beaten by the Taliban and knows many more who have been targeted.

Ziar Khan Yaad and his wife in Pakistan.

“We are the people who are working for the freedom of speech.… We are working for the rights of the people,” he says.

“If I go back home, I think I will be erased. I will be beaten again. Maybe they will kill me.… My family are not safe either.”

That is why, when he says IRCC told him his family was not eligible for resettlement, despite an initial email stating they might qualify, he was upset.

IRCC refused to answer questions about Yaad’s situation as it doesn’t comment on any specific cases.

He worries about the implications of this, as his parents, two sisters and brother, who remain in Afghanistan, have been harassed for Yaad’s journalism and his outspoken nature online.

“The Taliban do not accept (my writing), and they are very angry,” Yaad says.

But he refuses to stop talking.

On Twitter, on April 4, among other thoughts on the situation in his home country, he wrote: “Afghans are the most deprived and worthless people in the world.”

After the U.S. pulled out of Afghanistan on Aug. 31, 2021, about 600 journalists who had worked with U.S.-sponsored news organizations were left behind. Several Afghan journalists we spoke to with U.S. links have been redirected to Canada’s resettlement program.

The U.S. State Department declined to answer all questions on the partnership with Canada.

The journalist we have agreed not to name, who has just returned to Afghanistan, has been an international correspondent for 15 years and most recently worked with U.S.-based news agency InterNews.

While he has a passport, his wife and their three children arrived in Islamabad six months ago without valid visas or passports, leaving them ineligible for accommodation assistance. He says he has spent “all my personal money” in Pakistan, predominantly on hospital bills.

Afghanistan crisis: Canada to accept 5,000 Afghan refugees evacuated by U.S. military – Aug 31, 2021

When the man fled the incoming Taliban from the radio station he worked at in Herat, he jumped from a high wall and felt “a big pain” in his leg. Days later, when he arrived in Islamabad, he went to have it checked out in hospital. Doctors said his leg had to be amputated.

“But they said, ‘You have come too late, there is no solution,’” the man says.

That, coupled with the lung cancer he has battled for years, has left him pleading with IRCC for access to better medical treatment in Canada.

After hearing nothing since doing their biometrics three months ago, the man returned to Afghanistan in an attempt to secure visas and passports for his family. While attempting to access the passport office, which he says the Taliban closes sporadically, he is hiding in his home. He says before he left the country, the Taliban came to his house twice trying to find him.

Watching Ukrainian refugees receive visas within weeks has been painful, he says, and there is “visible discrimination” from the Canadian government.

“My safety is a big problem here,” he says.

“It’s a very bad feeling. My whole lifetime I won’t forget it.”

Ahmad Yazdani and his family say they have been waiting in Pakistan for resettlement for seven months.

Another journalist, Ahmad Seyar Yazdani, says he has been in Pakistan for seven months waiting for resettlement to Canada. He was a correspondent for several U.S. news outlets and says he was threatened with letters from the Taliban for his work.

He fled Afghanistan for Islamabad in the middle of the night with his wife and two-year-old son in December and did his biometrics for Canada on Jan. 18.

Yazdani sold his garden in Afghanistan to pay for his rent in Pakistan and borrowed money from family members to make ends meet. But money is fraught for his family, too – his two sisters, one of whom is a doctor and one a teacher, have been barred from working under the Taliban regime.

“We have big financial problems in Pakistan. Right now we are depressed and stressed. Our money is going to finish soon. We don’t know how to go ahead,” Yazdani says.

The Canadian government has faced heavy criticism for the pace at which it is processing Afghan applications for resettlement. Officials have been adamant, though, that Canada is doing what it can under challenging circumstances.

On March 31, dozens of Afghan interpreters that worked with Canada’s military initiated a hunger strike on Parliament Hill to demand that the federal government do more to help their families left behind in Afghanistan.

Though a family reunification immigration stream was introduced in December, there have been no arrivals under the policy to date.

Sean Fraser, Canada’s minister of immigration, refugees and citizenship, defended the government’s work during question period in the House of Commons last week.

“We’re going to continue to do more, no matter the scale of the challenges, we are going to make good on our commitment to the individuals who want to bring and reunite with their families here in Canada,” he said.

But no concrete action was promised.

Canada has received 112,000 applications for Ukrainian refugees, minister says

Days later, the House of Commons immigration committee voted to issue a public statement, urging the government to provide the same special immigration measures it has extended to Ukrainians to refugees from other regions.

The Canada-Ukraine authorization for emergency travel has offered Ukrainians fleeing war a fast-tracked application process into Canada, with more than 26,500 applications approved to date.

But IRCC is adamant that Afghanistan and Ukraine are not comparable warzones.

Isabelle Dubois, IRCC spokesperson, said the process for Ukrainians was different as it is a temporary residency pathway and not the “permanent resettlement pathway” other refugees undertake.

“IRCC is fully equipped and has the resources to handle multiple initiatives,” she says.

Russia-Ukraine conflict: Trudeau, immigration minister say they’re fast-tracking applications for Ukrainians – Feb 28, 2022

Dubois would not say what the average processing time for Afghans is under the special immigration measures, stating that it varies on a case-by-case basis, but said the delays were due to “obstacles facing us in Afghanistan that were not present in other large-scale resettlement efforts.”

“The bottleneck is not the processing capacity of the government of Canada – it’s situational and environmental factors on the ground in Afghanistan, including where approved applicants are currently located and their access to travel documents and the ability to leave the country.”

There is no financial assistance available for refugees who are approved but still waiting for resettlement. However, IRCC has contracted the International Organization for Migration (IOM), a UN agency, to provide accommodation and co-ordinate flights for refugees.

Read more:

The Russia-Ukraine information war — How propaganda is being used in two very different ways

More than 1,400 Afghans are currently receiving accommodation assistance in Pakistan, an IOM spokesperson says.

However, to be eligible, there are strict criteria.

A person must “hold legal status in the country they have entered, are eligible for the program and have submitted a complete application,” IRCC says. It means many who fled Afghanistan without proper documentation cannot access this service.

Abdul Rahman Amiri, the brother of an interpreter for the Canadian Armed Forces in Kandahar, is one of many who have been declined this assistance.

‘Our patience is over’ says Afghan waiting for IRCC application while enduring financial difficulties

Amiri arrived in Islamabad on Nov. 25, with his brother and 14 members of their family. Five of them qualified for IOM accommodation and the remaining 11 sleep on the floor across two rooms and a hallway in the cheapest building they could find. They completed their biometrics on Dec. 10 and say they have heard nothing about their situation since.

Amiri says their money is fast running out and for the last month, they have been eating just one meal a day. His wife has been battling malnutrition and struggles with other health issues. He says his financial situation may soon force the family to return to Afghanistan.

Amiri’s wife has been ill with malnutrition and health issues. He says he cannot afford to pay for her medicine.

“Alhamdulillah, here we are safe, but … after more than four months, our financial situation is altered and so is our mental situation. We are here with a big depression,” Amiri says.

“It’s very difficult for us when we see our kids, when we see the women, when we see everything but cannot do anything, we are not able to do anything. This is so, so difficult. We are not in a good situation.”

Abdul Amiri says 11 members of his family are sleeping on the floor across two rooms and a hallway while they await resettlement in Canada.

Amiri says he just wants to know how long he will be waiting.

“It’s the only thing that we need in this time, how much time do we wait? Then we can decide for our families. We can decide what to do. But … we don’t have any information about our applications after four months.

“Just give us some updates. What should we do? Our patience is over. Just give us some convincing advice.”

Experts say more must be done to help Afghans in limbo, as just because they have made it out of the country does not mean they are no longer in danger.

The deputy director of emergencies at the Committee to Protect Journalists, Kerry Paterson, says the group has helped 60 journalists flee Afghanistan.

However, she says NGOs can only do so much to support vulnerable Afghans and global governments now need to step up.

“In the days, weeks and months following the U.S. departure, CPJ received tens of thousands of requests for emergency assistance,” she says.

“(But) we cannot replace the role of governments — NGOs cannot issue visas, grant asylum or provide long-term solutions for people whose lives have been completely upended.”

Ontario announces $300M more in support for Ukraine, priority travel processing for refugees

For this reason, CPJ has been advocating for emergency visas to be introduced globally for journalists fleeing dangerous situations. Paterson says the situation in Afghanistan, and now Ukraine, underscores just how important these visas are.

Cassandra Fultz, managing partner of Doherty Fultz Immigration and a regulated Canadian immigration consultant, says directly after the fall of Kabul in August, her firm was receiving 10 to 20 emails per day from Afghans, many of whom had worked for the Canadian or U.S. government. However, this has now decreased to about three to four emails per week.

Fultz says that due to COVID-19, wait times have ballooned for many types of visa applications and frustrations are across the board. However, she says Afghans must be prioritized due to their vulnerability.

“This is life and death for people in Afghanistan, every day matters and every day counts.

“We have more questions than answers at this point and the questions are not being addressed. Why are flights taking so long to be organized when biometrics are done?”

Fultz says IRCC’s assertion that Ukrainians can be prioritized due to their resettlement being temporary is a moot point as this option was not offered to Afghans.

“I understand that security is a real concern (for IRCC). But that doesn’t help the people on the ground. What is being done to address this? What is being done to safeguard these people’s lives?”